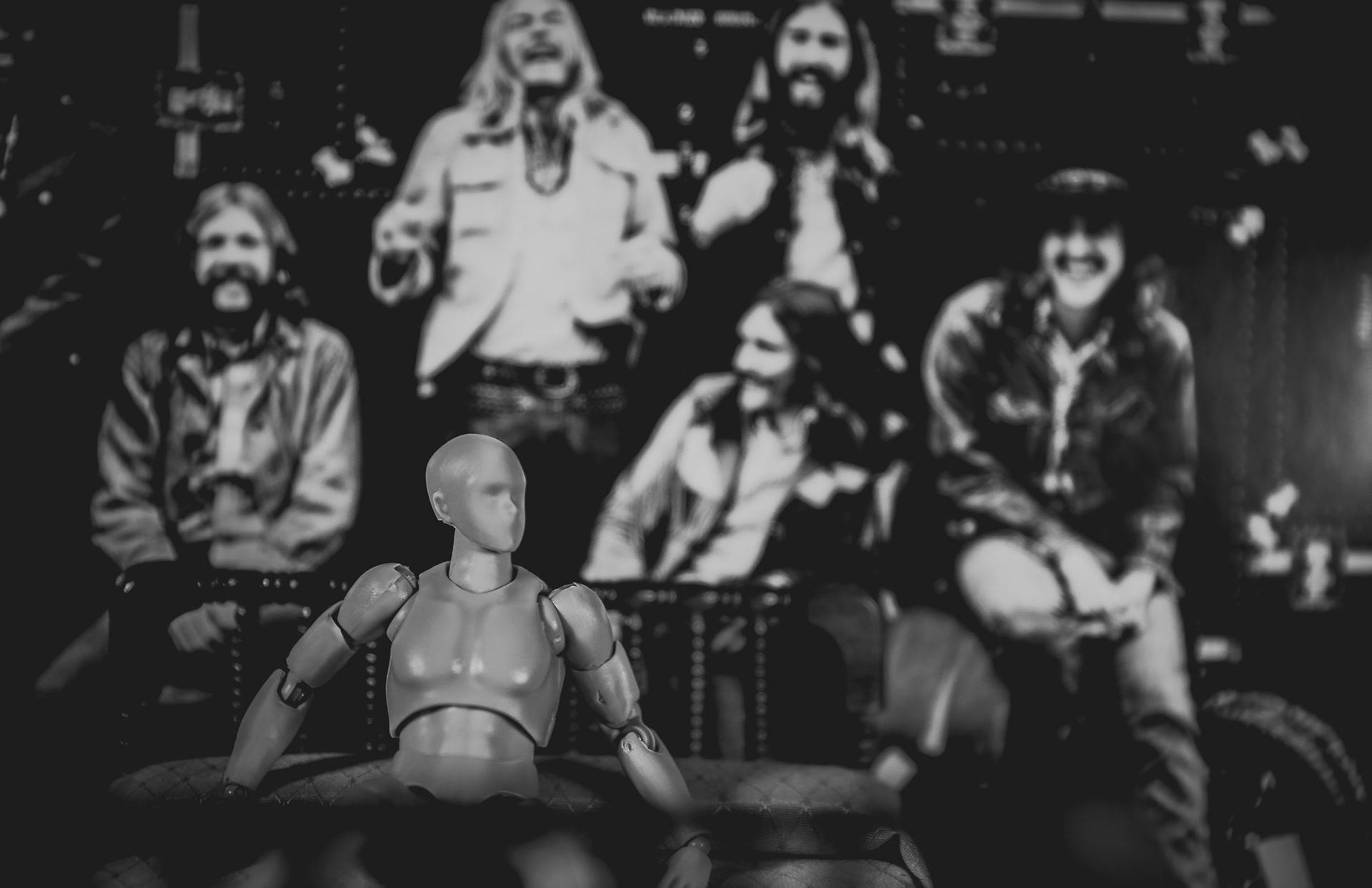

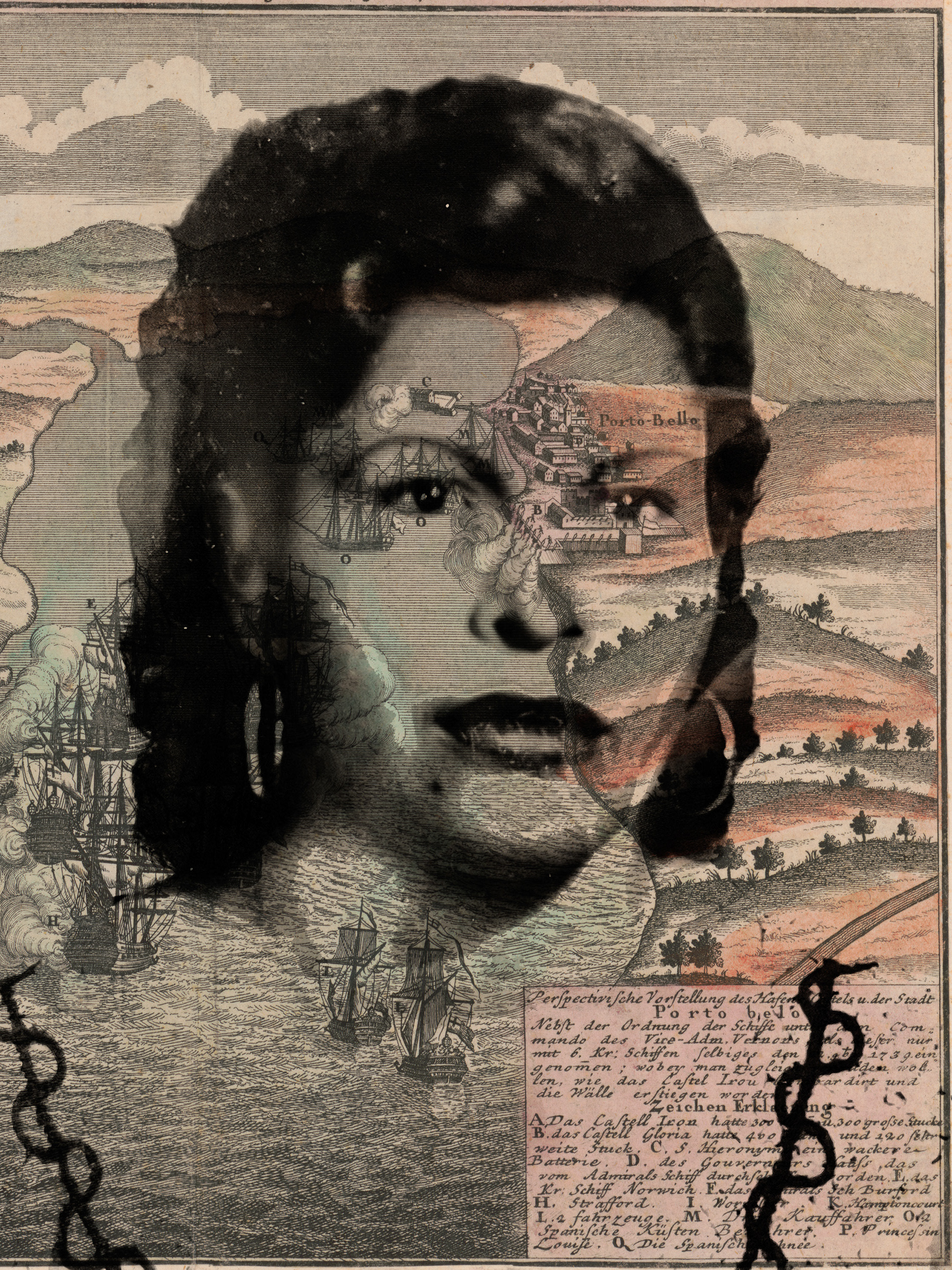

Collage of my biological father, Fernando, and I at (roughly) age 12.

People often describe growing up without a biological father as living with a hole in the heart... or a broken heart. Those metaphors never felt accurate to me. A hole suggests emptiness. What I recognize instead is a bruise—something formed through contact, something tender, something darkened by pressure. A bruise remembers where it was touched. Pressing it hurts, but it also confirms sensation remains.

This is the bruise I carry from my father.

Pressing it is how I trace the history of his absence,

of the half-formed relationship

that never was,

and of the

myths and memories

I built to fill in the gaps.

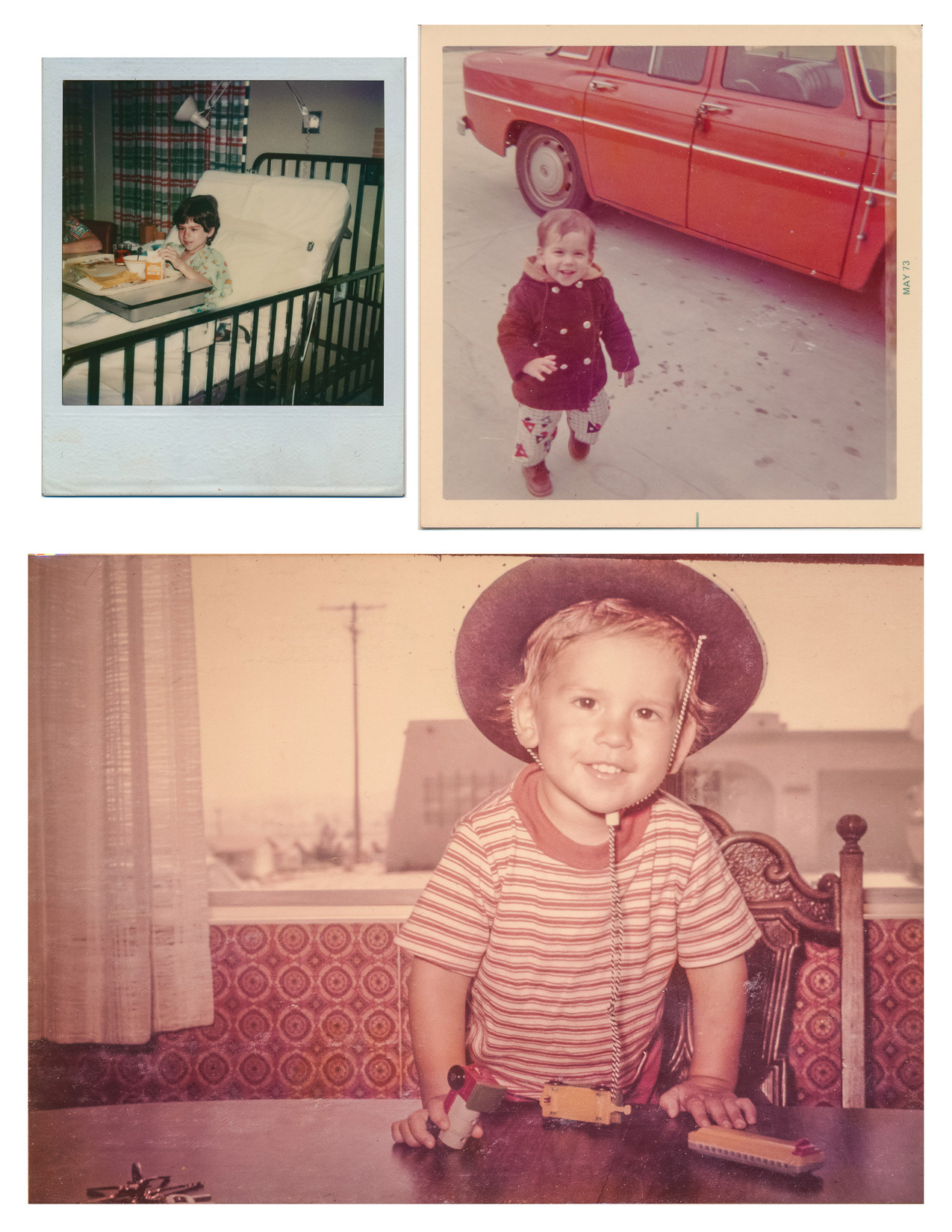

On February 17, 1971, my mother, Pamela Jean Cochran, turned eighteen. Two weeks and one day later, she traveled roughly three hours from Hampton, Virginia, to Elizabeth City, North Carolina, accompanied by her sixteen-year-old sister, Catherine, to be married to Fernando Rivera Jr., who was twenty at the time. The wedding was quiet, out of state, and uncelebrated. My mother returned home and completed her senior year of high school as a secretly married young woman. Within weeks, she was pregnant.

Taking the leap together.

Pregnant and alone.

For several months, Pamela carried both the marriage and the pregnancy largely alone. Fernando eventually revealed the truth to her parents—not privately, and not gently. At her high school graduation in late spring 1971, he announced to my maternal grandparents that Pamela was married, pregnant, and moving in with him that night. The declaration was public, abrupt, and final. Whatever agency my mother still had in the matter evaporated in that moment.

The marriage deteriorated quickly. My mother discovered Fernando cheating on her. She learned that he was selling marijuana illegally. When she flushed his stash down the drain, he struck her. Before I was born, my mother began the process of divorcing him. Two weeks before my birth, she left Fernando and returned to live with her parents. She was eighteen years old, visibly pregnant, preparing to give birth without a partner. Whatever possibility of reconciliation might have existed ended before I entered the world.

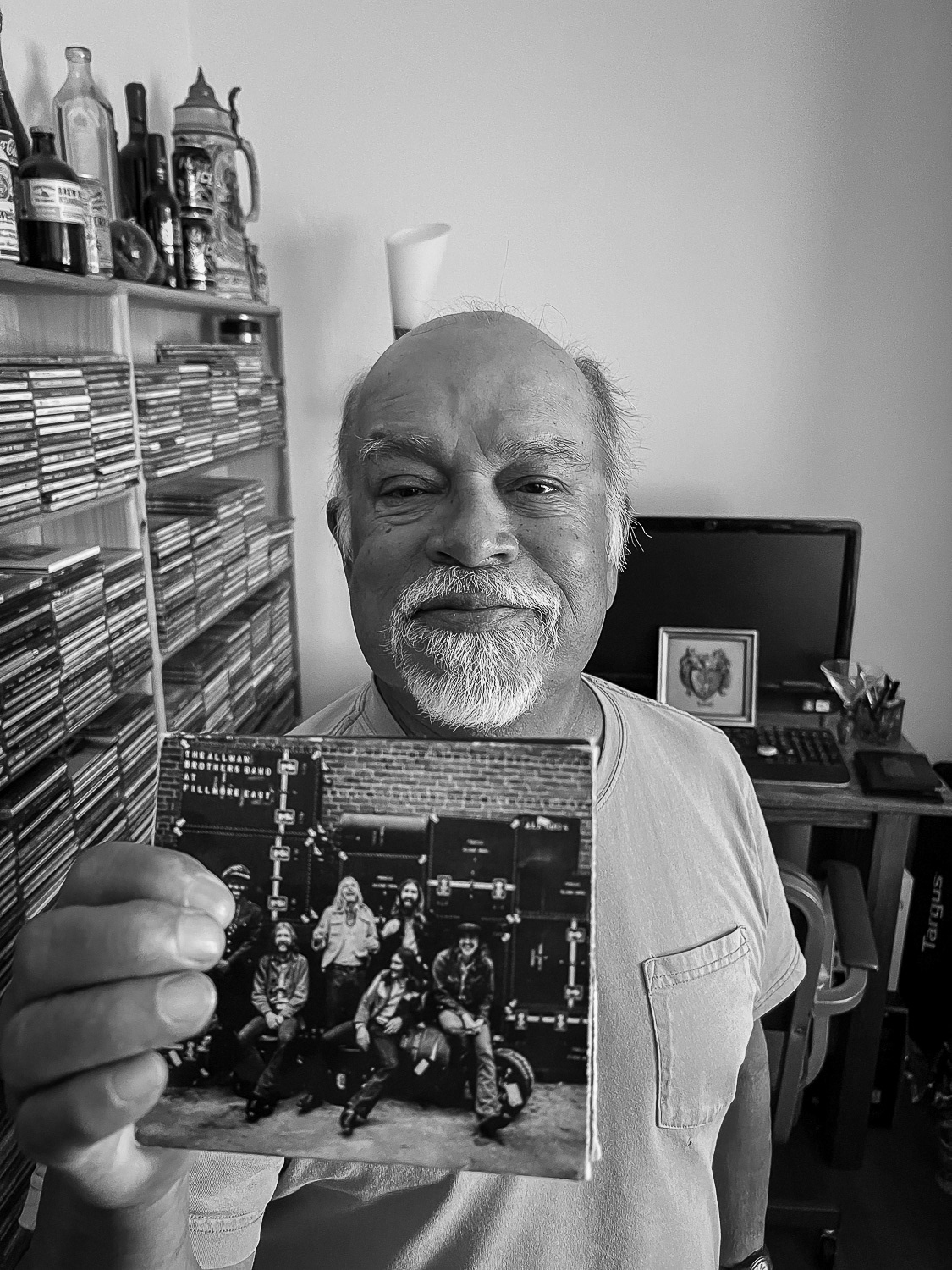

I was born on December 12, 1971, at Dixie Hospital in Hampton, Virginia. That same day, Fernando attended an Allman Brothers concert at the newly opened Hampton Coliseum. He later claimed that he went to the hospital afterward, but my grandmother prevented him from seeing either my mother or me. I have no memory of this, only competing versions of the story. What remains clear is that he was not present at my birth in any way that became part of my lived experience.

Collage of my first photo, birth certificate and parents' artfully torn marriage license.

After I was born, my mother remained with her parents, navigating new motherhood and the aftermath of a marriage that had collapsed almost as quickly as it had begun. By August of 1972, my maternal grandparents moved from Virginia to San Marcos, California. With few alternatives, my mother followed them. I was eight months old when we crossed the country. That move marked the beginning of a long and sustained absence. My biological father became someone who existed largely in explanation rather than experience.

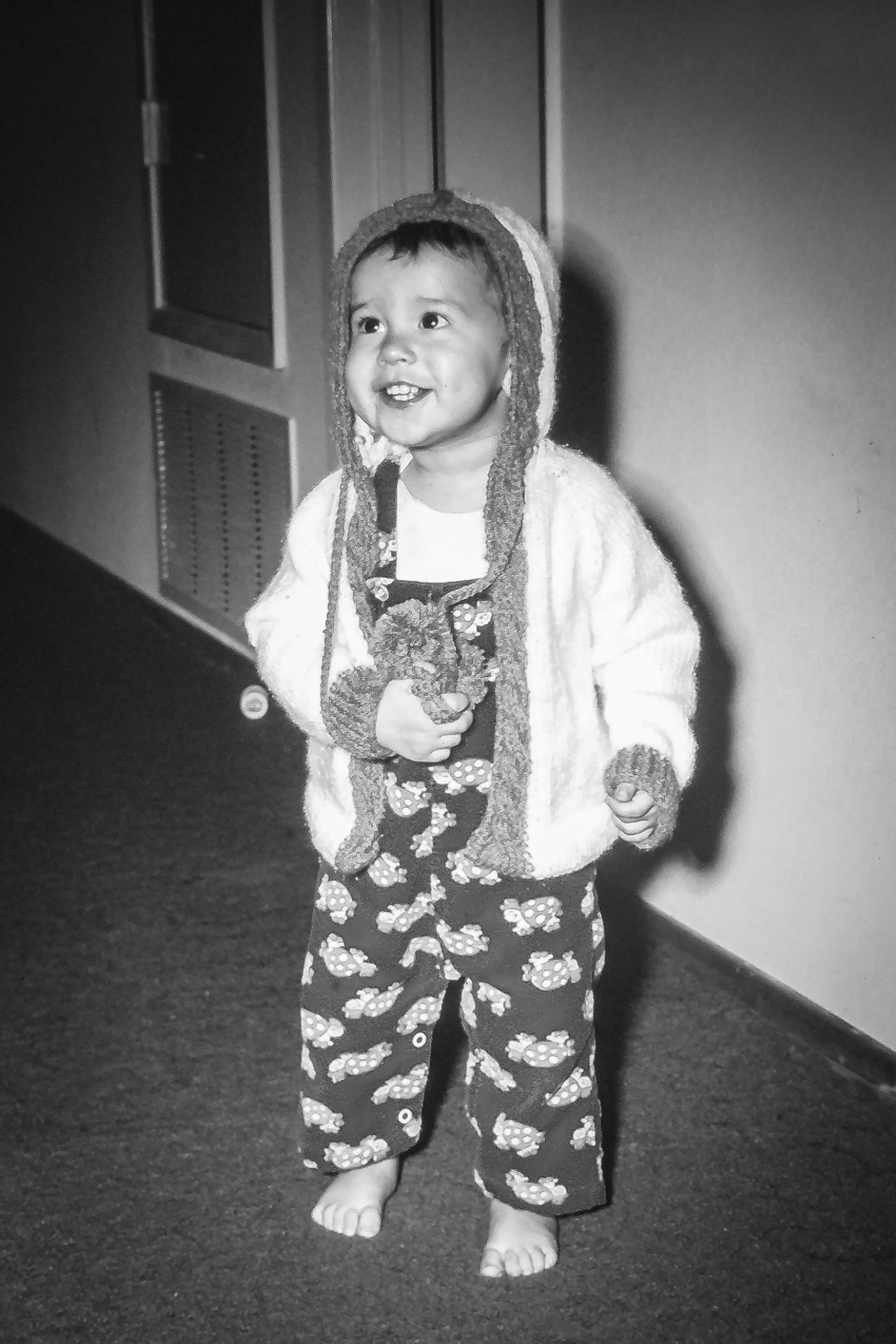

Once she was settled, my mother found work and eventually moved us into our own place. It was a government-subsidized apartment—two bedrooms, modest and spare. I’ve always been struck by the fact that because I was a male child living with a single mother, we were allotted the extra room, as if the gender of a two- or three-year-old mattered in the slightest. It’s a small, bureaucratic detail, but it reveals something about the era: how deeply and casually assumptions about gender, propriety, and family structure were embedded into policy. Even then, my life was being shaped by decisions made in absent rooms, by people who would never meet us.

There were no regular phone calls, no visits, no shared holidays. Whatever relationship might have existed between Fernando and I was mediated through adults, documents, and silence. There was one exception: when I was around three years old, Fernando visited us in California. I have no memory of the visit itself, only a small number of photographs—images that function less as recollection than as proof. In them, he holds me. I look tentative, as if unsure how to position myself in relation to him.

I do remember the few details that carried emotional weight. He put his dirty boots up on my mother’s coffee table and shaved in her sink without cleaning up afterward. To my young mind, these gestures—messy, intrusive, inconsiderate—were the reasons he left. Little did I know then that his true intent had never been to reconcile with me, but rather with my mother. When he saw that was not going to happen, he disappeared from my life a second time. After that, silence resumed.

When I was eight years old, Fernando called again. The call was not initiated out of curiosity or care, but as a condition: my stepfather, Les Zufelt, wanted to legally adopt me, and Fernando agreed only if he could make this final contact. I remember the call as confusing rather than comforting. Instead of reassurance, he said things like, “Don’t ever forget you’ve got my blood in you.” At that age, I didn’t know how to interpret a statement like that. It sounded important and ominous at the same time—less an offer of connection than a reminder of claim.

After that phone call, Fernando disappeared entirely. Les adopted me. My name changed. My daily life stabilized. I was raised by a man who chose presence over biology, consistency over mystery. Still, my biological father lingered—not as a person, but as an unresolved force. He existed in the background of my understanding of myself, shaping questions I didn’t yet have language for. My mother shared information sparingly. Details arrived out of sequence, often softened or incomplete. In the absence of facts, I filled in the gaps myself. Myth formed where memory could not.

During those 40+ years of silence, he had to think about me every now and then... right?

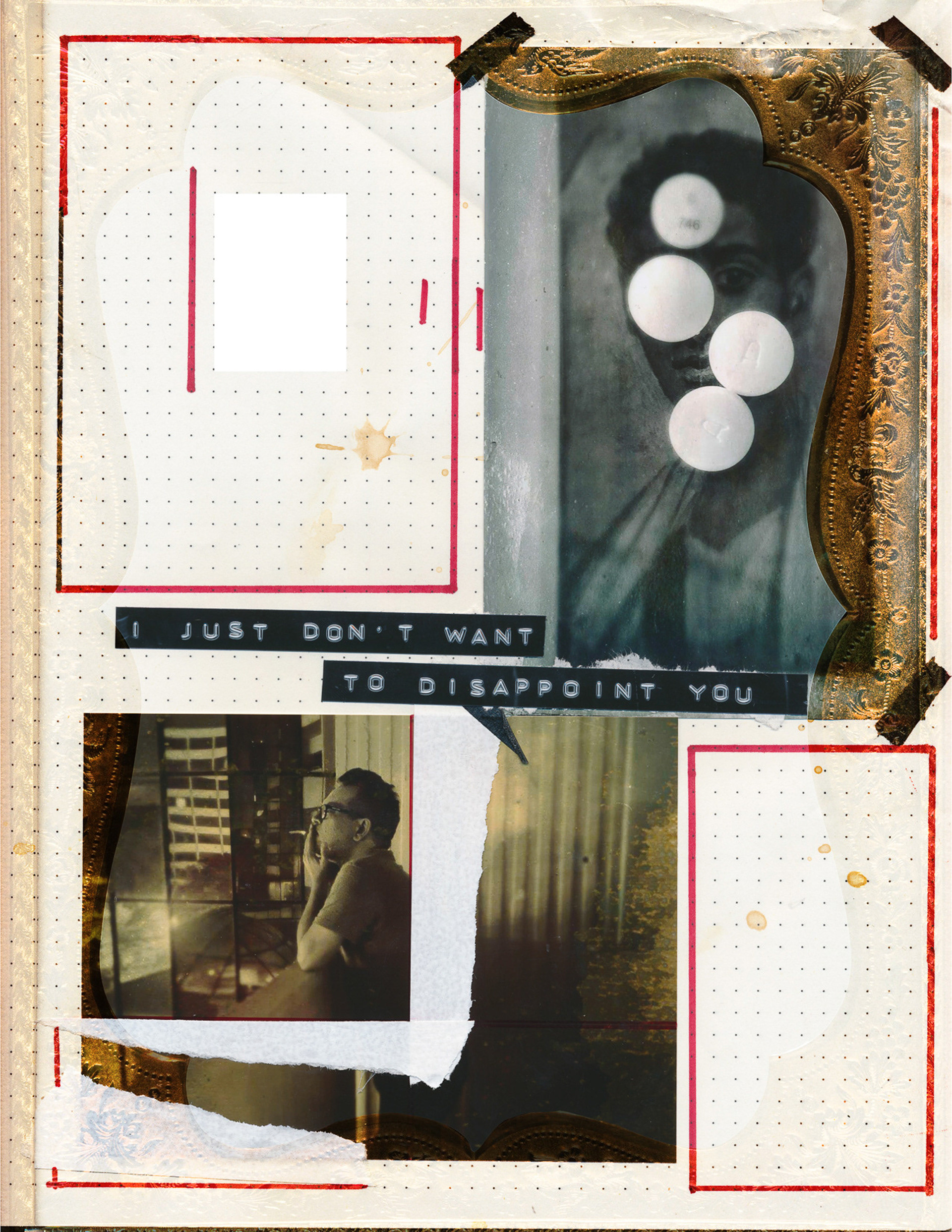

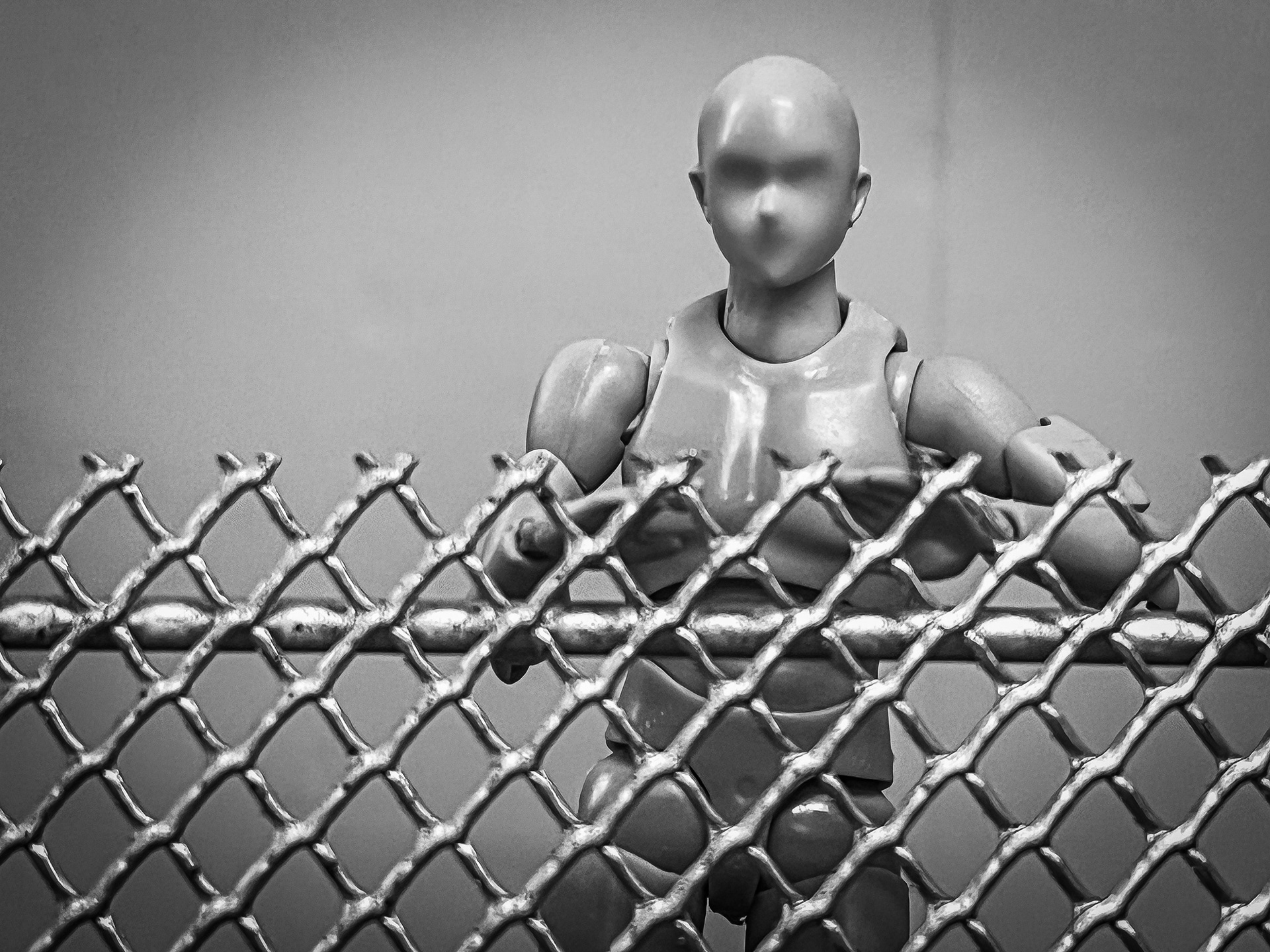

As a child, I constructed my biological father from fragments: a name, a birthdate, two handwritten letters he sent to my mother in 1973 that were intended to be shared with me someday, and a single photograph of him with a young cousin balanced on his knee, a puppy in his lap, and a Christmas tree in the background. These artifacts carried disproportionate weight. Without lived experience to ground them, they expanded. Fernando became less a man than an idea—an explanation for things I didn’t yet understand.

Artifacts

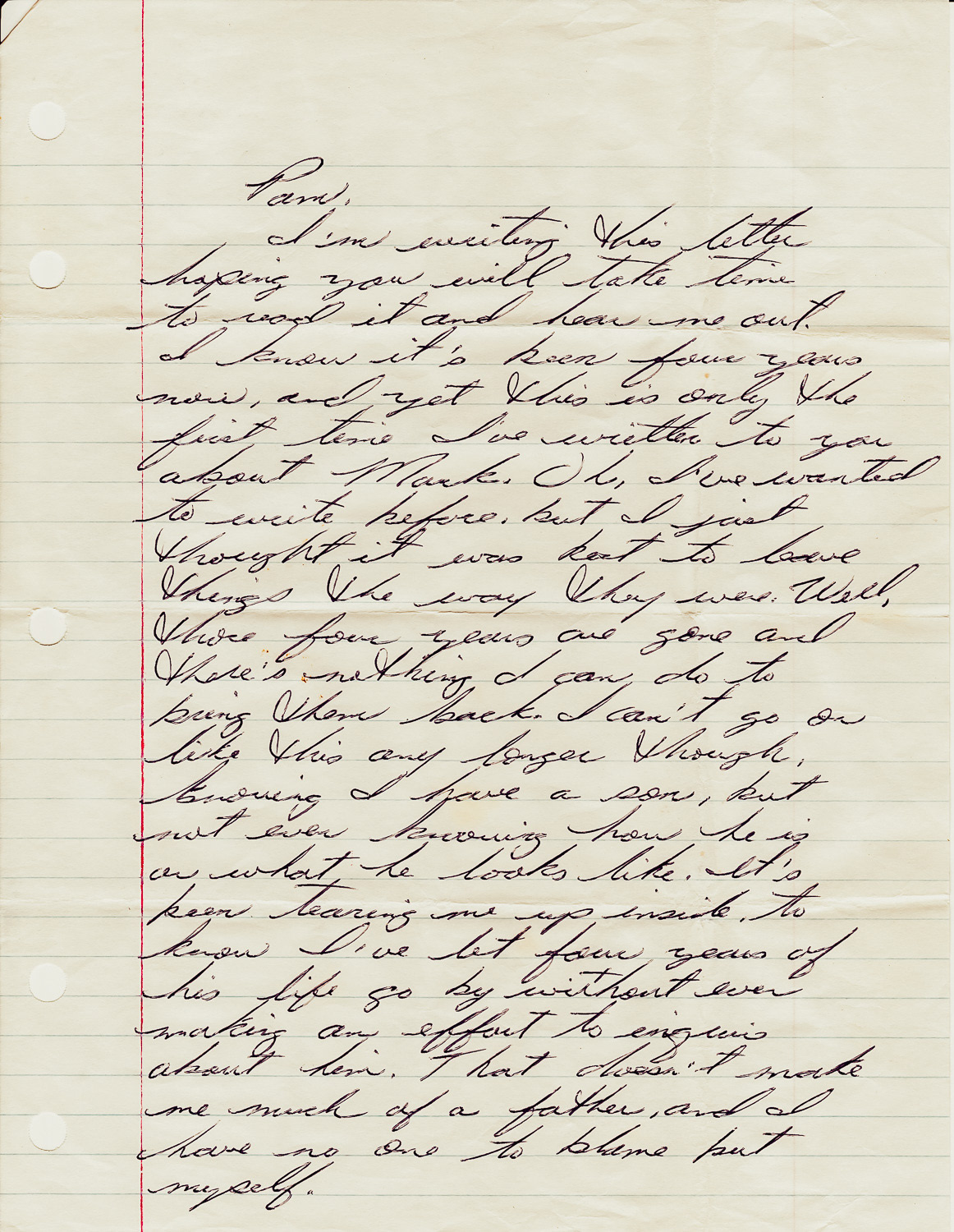

The Letter

For much of my adult life, Fernando existed only at a distance. Every few years, I searched his name online to see if he had died. When he hadn’t, I returned to not knowing. In my forties, as health concerns emerged and questions of genetics and inheritance became harder to ignore, curiosity shifted into urgency. I didn’t want a relationship. I wanted clarity. I wanted to know what lived in my body that had come from him. At my wife’s suggestion, a private investigator was hired to locate him quietly. The intention was limited and private. Instead, through a series of errors, the investigator revealed both herself and her client. Fernando—still alive—was contacted directly. Confused and understandably alarmed, he called my wife, an attorney practicing on the other coast, demanding to know why she was tailing him. With no way out, she told him the truth: she was married to his son.

I tried to engage him with talk of my past and present...

but he just wanted to talk about himself.

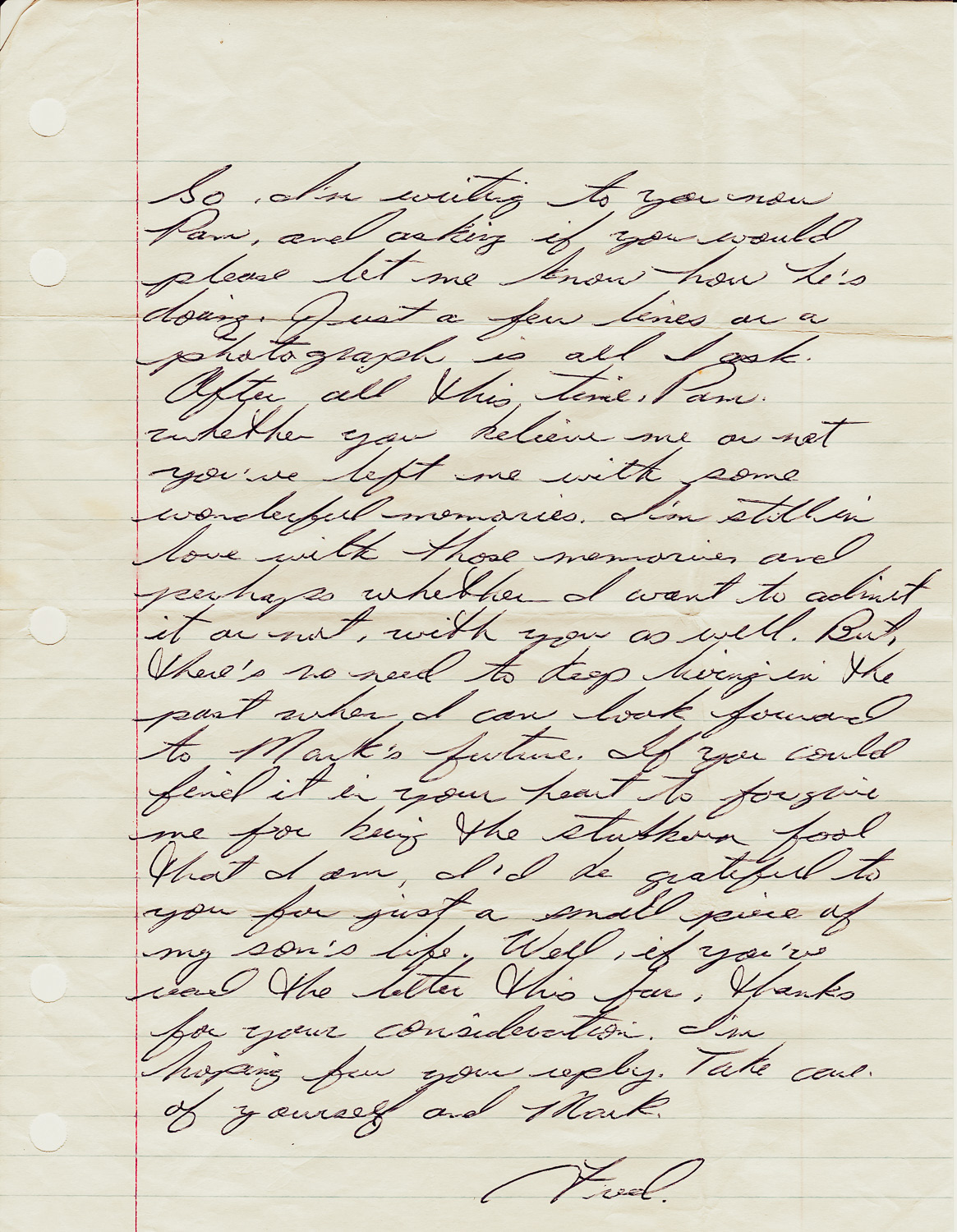

After two years of sporadic calls and a few volatile voicemails, I eventually met Fernando, his wife Jeri, and a number of Tias (aunts) and cousins. Still, there was no resolution. No apologies, just a lot of half attempts at feeble explanations that trailed off or went nowhere. I remember his final hug, when he whispered in my ear, “I just don’t want to disappoint you!” I felt a little embarrassed by the sentiment—we had little in common, and I doubt we would have been friends were it not for the genetic link.

That bruise—the evidence of absence, of partial encounters and lingering questions—remains with me. Pressing it does not heal it. Pressing it does not erase the past. But it reminds me that sensation, memory, and feeling persist. The bruise is the record of contact, both failed and fleeting, and pressing it confirms that I am still here, still feeling, still tracing the lines of connection that were never fully drawn.

More images:

Young Fernando.

Pam and Fernando met at courted at an all ages hangout called "The Cafeteria"

Fernando was very proud of his former playboy status. (Faces removed for privacy.)

Since he didn't have a photo of my mother in his collection, I kindly (and digitally) added one.

Fernando decided to tell Pam's parents everything, without consenting with her first.

Digital collage of my paternal grandmother, Maxima and her homeland, Panama.

Our private investor forgot the "Private" part.